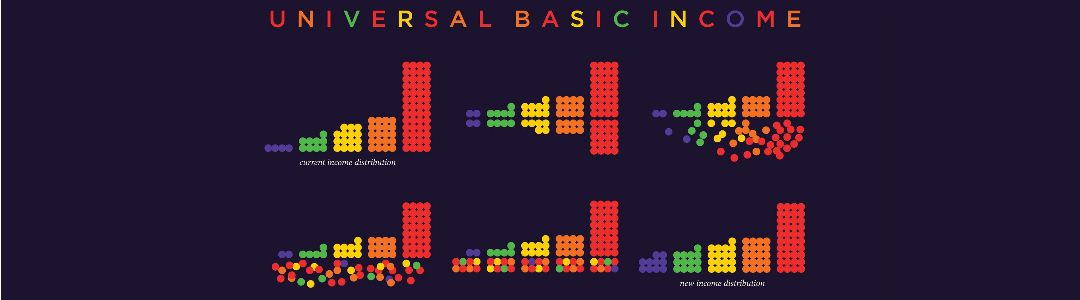

The idea and rationale for a Universal Basic Income (UBI) scheme for India has finally found a mention in this year’s Economic Survey 2016-17, albeit as a topic for discussion only. The section on UBI has provided an explanation for the concept, its various benefits as well as challenges.

Globally too, the concept has attracted greater attention in recent times driven by the anticipation that technological disruption (robotic automation and artificial intelligence, others) would cause mass unemployment (extensive job losses) globally and especially in advanced economies. Hence, governments across countries are deliberating the option of UBI to provide citizens a guaranteed amount of income, irrespective of their economic or employment status.

While in the developed economies it is being viewed as a solution to deal with technology-induced unemployment (projected to grow), in other economies, it is perceived as a means to reduce inequalities and increase consumption demand. For India, the UBI has been proposed as an unconditional uniform stipend (cash) which could be paid to citizens through direct transfers to their bank accounts, which could empower the poor to make their own economic decisions and choices while promoting social justice.

The UBI scheme would also be easier to administer compared to the myriad of welfare programs currently being administered by the government. It is seen as potential solution to the problem of misallocation, leakages and corruption that plague the country’s current social welfare programmes and streamline distribution of aid to the poor. As India adopts rapidly evolving technologies, UBI would also aid in addressing expected unemployment arising from obsolescence of workforce.

Conceptual case for Universal Basic Income

Universal Basic Income is premised on the idea that a just society needs to guarantee to each individual a minimum income which they can count on, and which provides the necessary material foundation for a life with access to basic goods and a life of dignity. A universal basic income is, like many rights, unconditional and universal: it requires that every person should have a right to a basic income to cover their needs, just by virtue of being citizens.

Rationale for Universal Basic Income

India at present has many different welfare programs administered by the government that are targeted at the poor; currently there are around 950 central sector and centrally sponsored sub-schemes in the country accounting for 5.2% of the GDP by budget allocation (Budget 2016-17). In addition, there are more schemes at the state level and most of them have been in force for a long period of time. Implementation of these schemes is riddled with various problems including misallocation, targeting–inclusion and exclusion errors; leakages- wastage and inefficiencies (corruption) in the delivery system; no uniformity in implementation across states as richer and better administered districts are able to implement more effectively; higher administrative costs; some of these schemes involve subsidies which distort resource allocation (water, electricity subsidies) – non-poor benefit relatively more from the subsidies; amongst others.

The Economic Survey has presented UBI as a single scheme which could replace this myriad of welfare programs with a simple unconditional cash transfer to every citizen paid at regular intervals. It states that as the transfer would be done directly to the accounts of the beneficiaries there would be reduction in system leakages and reduce misallocation (deal with exclusion errors) to districts with less poor and given the universal nature of the scheme it would reduce the administrative burden and costs associated with it. However, last mile connectivity would still remain a concern as beneficiaries would have to access their bank accounts.

Cost of Implementing UBI

The cost for implementing the UBI, which will replace all other welfare schemes could be around 4.9% of GDP, according to the estimates provided by the Economic Survey. This would be lower than the current cost of welfare programme, which, as mentioned earlier, is about 5.2% of GDP. The cost has been arrived at by considering certain assumptions. Considering that eliminating poverty completely could be a costly affair, the survey has selected a target poverty level of 0.45% and has computed the 2011-12 consumption level of people at this threshold level.

Based on this level of consumption, the amount of fixed income or stipend required to bring an individual above the poverty line of Rs. 893 per month (Tendulkar Poverty Line for 2011-12) has been calculated, which has worked out to be Rs. 5400 per year. After taking into consideration the effect of inflation, the minimum income amount for the year 2016-17 has been estimated to be Rs. 7620 per individual per year. The survey however has assumed a quasi-universality rate of 75% while arriving at the total cost of implementation of the scheme.

The graph captures the UBI for various poverty levels and the associated fiscal costs.

The survey has further suggested that the UBI amount would have to be revised from time to time as its real value would depend and vary according to the prevailing inflation in the economy. The survey therefore proposes indexing it to prices so that the amount gets revised periodically.

Prerequisites for successful implementation of the UBI, however, would be the functional trinity of Jan-Dhan, Aadhaar and Mobile (JAM) which could be used to provide funds to each individual directly into his or her account and an understanding on the share of Centre and State in the funding of UBI, the survey adds. It suggests that initially, a minimum UBI could be funded wholly by the Centre and gradually the Centre could adopt a matching grant system wherein the Centre matches the State for every rupee it spends in providing a UBI.

Views on the UBI Scheme

As with any new idea, the UBI has also received its fair share of remarks in favor and against the concept. Those in favour view it as giving the individual freedom to spend with dignity, independent of his/her capability to earn in the absence of employment. They believe it would also reduce poverty and inequalities. As individuals would be paid as per the UBI scheme (not households) it could enable women empowerment and possibly contribute to effective spending on children (nutrition and education) and their businesses. UBI could also relieve a part of the credit constraints for self-employed small producers amongst the poor.

Two sides on the debate on UBI

- Poverty and vulnerability reduction

- Choice -Individual could spend as per his/her choice

- Better targeting of poor

- Insurance against shocks

- Improvement in financial inclusion

- Psychological benefits -reduce pressure of finding a basic living

- Administrative efficiency

- Spending on wasteful activities

- Moral hazard (reduction in labour supply)

- Gender disparity induced by cash

- Implementation-stress on the banking system

- Fiscal cost given political economy of exit

- Political economy of universality –ideas for self-exclusion

- Exposure to market risks (cash vs. food)

In the next post in this series on Universal Basic Income, we will focus on Potential Issues with Universal Basic Income and International Experiences in the implementation of Universal Basic Income