While advantages of the UBI scheme are quite apparent, the critics of the scheme have also raised some valid points against it. The survey proposes that UBI replaces the welfare schemes such as MNREGA, Pradhan Mantri Gram SadakYojana, Pradhan MantriAwasYojana, National Health Mission, Swachh Bharat Abhiyan, SarwaSikshaAbhiyan, Mid-Day Meal Scheme, LPG Subsidy, Food Subsidy, Fertilizer Subsidy and every other centrally sponsored scheme and sub schemes in operation in the country. One major advantage of having numerous welfare schemes in place is that in case a scheme fails to deliver, the other schemes can compensate for that loss.

Moreover, all welfare schemes are not aimed at poverty reduction and hence pro-poor. For instance, subsidies on food and fertilizers benefit incomes of farmers and also aid in providing food at reasonable rates to people. In the event of situations like drought, famine, crop loss, natural and man-made disasters, in-kind benefits like food subsidy (PDS) are more effective than cash transfers. Similarly, MGNREGA provides employment to people and at the same time leads to creation of capital assets; the mid-day meal scheme provides children with food leading to improvement in nutrition levels. Objective of some other schemes involving provision of subsidies and tax exemptions is to stimulate growth or exports and be instrumental in bringing about a structural change. Similar is the case with schemes related to education and healthcare which would have an impact across generations.

In the event of the subsidies being removed, the government would have to ensure education and health to all citizens at nominal prices. The country could also witness increase in rail fares and water and electricity bills as well as fuel prices. Rise in fuel prices could make them expensive/unaffordable for the poor, who may then revert back to traditional fuels for cooking. Discontinuation of welfare programmes could lead to higher prices of essential commodities including food, thus effectively reducing the real income for the individuals.

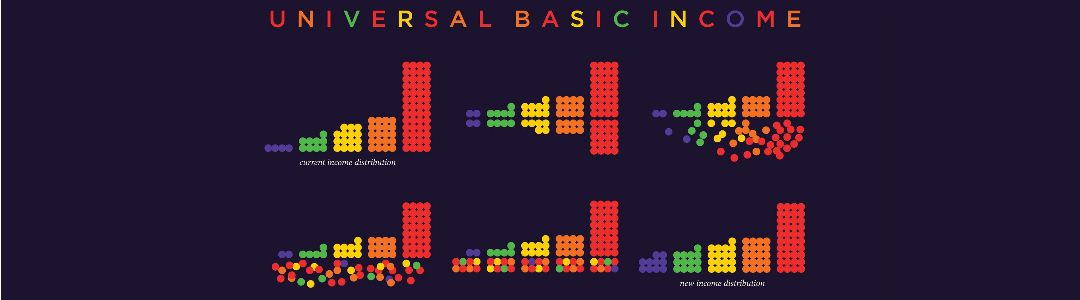

The UBI scheme is also expected to address the problem of targeting. However, with the proposal to adopt a quasi-universal approach (targeting only 75% of the population), the issues with targeting would still continue. On the contrary, if the scheme is implemented on a universal basis, it will lead to substantial reduction in the amount of per person income in case the overall outgo is maintained at the level achieved under the quasi-universal approach. On the other hand, if the income per individual is maintained at the present proposed level, then the overall outgo would increase substantially which would be economically unfavorable. Also, in case the scheme is made universal, even the rich and wealthy would receive cash transfers. It could also lead to diversion of spending away from crucial areas such as infrastructure, education and healthcare which are critical for long-term inclusive growth.

One other major argument against basic income is that the poor may spend it on alcohol, drugs and other unwanted activities; though this argument has been refuted by the findings of the pilot study conducted in rural Madhya Pradesh through the Self Employed Women’s Association in 2011 – ‘Madhya Pradesh Unconditional Cash Transfer Project’. Under this project, over 6,000 individuals were provided with the ‘basic income’ for duration of 12 to 18 months. Experiences across the world on the use of unconditional cash transfers have also shown that expenditure has been made on worthwhile goods and services.

Challenges to the Implementation of the Scheme

The proponents and those in favor would all agree that while the idea is well appreciated it does face various challenges and practical difficulties in implementing the scheme nationwide. With the implementation of Aadhaar and JAM, a large proportion of the country’s population has access to banking. However, given the relatively low density of banks and banking networks in remote rural areas, many of the individuals may not been able to access the money credited to their accounts. The smart phone penetration in the country may aid in tiding overall the problem of lower density of bank branches, however the costs associated with online transactions could prove to be costly for the rural household beneficiaries.

Computation of the UBI has been done on the basis of the poverty line as per Tendulkar Committee. In India even though the official poverty line is very low, around one-fifth of the population still falls below the BPL. Also, the line differs for urban and rural areas. In India, majority of the workers are in the informal sector and largely self-employed without any income data which could render testing (for poverty) difficult.

There could be resistance with respect to discontinuation of the welfare schemes, as it is easy to introduce schemes in the country, but difficult to exit them. Concerns remain whether UBI would replace all the welfare programs in place or just supplement them. In the event of welfare schemes and UBI being implemented on parallel lines, it could lead to unsustainable budgetary burden.

Lastly, the idea of ‘one size fits all’ does not apply and depending on the situation, different schemes could work out best. Ready access to markets would play a crucial role in the implementation of UBI.

Globally, while countries and states have implemented basic income schemes or schemes similar to that (please see Annexure-International Experiences), there is no precedent of a major economy implementing a UBI scheme and hence India would have to learn on the work.

Thus, Universal Basic Income as an idea is well received and appreciated. However, given the challenges and issues concerning its implementation it needs to be well discussed amongst the various stakeholders to work out the appropriate scheme for India. As the survey states, UBI is a powerful idea whose time even if not ripe for implementation is ripe for serious discussion.

Read the first part of FICCI Research Team’s Economic insights series on: Universal Basic Income